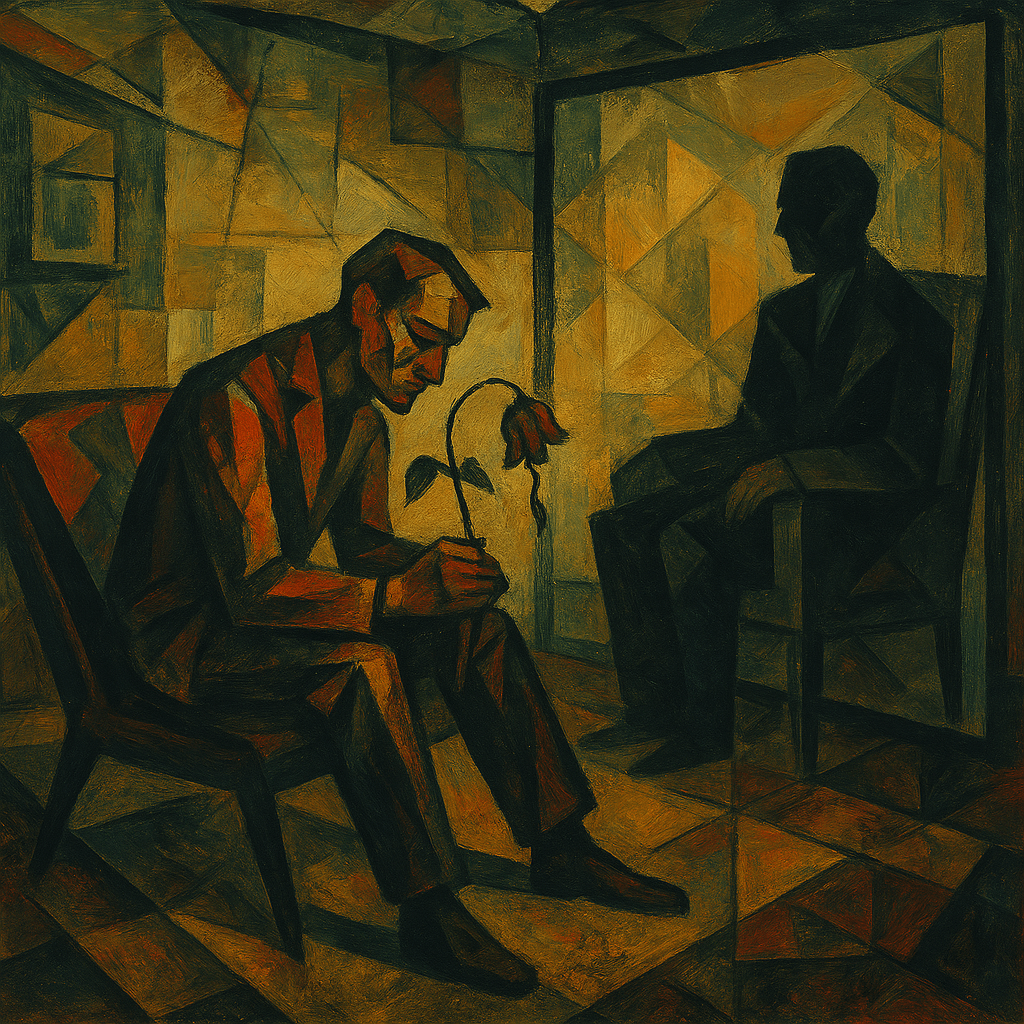

In his 21st seminar, Jacques Lacan is known to have said that his years of experience as a psychoanalyst taught him one thing: that “feelings are always reciprocal.” This might sound like good news for the hopeless romantic. Many rejected lovers carry the certainty that, in their hearts, their cold beloved actually harbors feelings of love for them. They are convinced this must be the case because they themselves feel love. They are duped by their love.

Quite expectedly, this hopeless idea has drifted into the jurisdiction of those whose craft operates on the premise of love: here, I speak of psychoanalysts. I won’t delve too deeply into this, as I believe one does not need a deep dive to recognize the critique. But I refer here to analysts who operate on the premise that the feelings—and, for that matter, also the ideas attached to feelings—that drift into their altered state of attention are fruits of the emotive reciprocity the hopeless romantic religiously attests to. Clearly, I am speaking here of the “counter” force to the force of the analysand’s love: the counter-love, i.e., countertransference. So you see, contemporary analysts often operate on the assumption that the analysand’s dispositions—mostly unconscious—authentically reciprocate themselves on the screen of their observing eye, or ear, or heart.

However, a few lines later, this statement is immediately qualified by Lacan, who adds that he said this to people who “as usual understand nothing of what I say.” He then explicitly states, “It’s not because one loves that one is loved. I never dared to say such a thing.” Lacan clarifies his position by explaining that “when one loves, one is made enamoured.”

What does this mean? Lacan suggests that, while the act of loving creates a state of being-in-love for the person who loves, it does not guarantee a reciprocal feeling from the object of their love.

Therefore, while Lacan is quoted as saying that feelings are always reciprocal, the context and his immediate correction indicate that he does not actually hold the view that love or feelings are necessarily mutual. Instead, the emphasis is on the effect of love on the subject who loves, rather than a guarantee of reciprocation from the other person.

This clinical observation becomes self-evident if you think about it. But perhaps it is even clearer when we think on the opposite side of the affective coin, shifting our focus from love to hate. After all, when one truly hates another person, this installs an effect in one’s life through which this person feels hated by the other. No one really hates without feeling somewhat hated. This logic also operates in romantic relationships, or in the relationship between children and their parents: hate is sometimes felt in its most vicious intensity when one feels loved.

Drawing on Lacan’s nuancing of his observation, we learn something about the work of psychoanalysis. The idea that when someone loves, they are “made enamoured” highlights that the experience of being in love is something that happens to the analysand who loves, regardless of whether that love is returned. This clarifies that being enamoured is a consequence of loving, not necessarily of being loved—a distinction crucial for understanding the dynamics of transference within a psychoanalytic framework.

Lacanian psychoanalysis shifts our understanding of the transference from a symmetrical, reciprocal model of love. And it has many clinical ramifications that are very important. However, I will only present two. The first is a fact derived from clinical experience, a fact that Freud accentuates in his paper on transference: the fact that the analysand’s transference always surprises. The analyst can’t really predict it or know when it will pop up or why. Sometimes it is even shocking, when the analysand all of a sudden confesses that in fact it is love which is at stake. A very hot one.

The second is the fact that nothing in the affective or ideational state of the analyst reciprocates that state in the analysand. In fact, when there is such reciprocation, we can only address it as a hindrance to the listening the analyst is supposed to provide. In other words, when the analyst reciprocates love, analysis becomes hopeless. It can only follow a path toward the disillusion of love, whereas it is intended to lead love toward transformation.

Lacanian psychoanalysis offers analysands a unique type of love relationship—one they cannot find with their romantic partners, their friends, and not even with their psychotherapists. Psychoanalysis offers a non-reciprocal love. It abides by the idea that only this non-reciprocality can lead to an effect that we call psychoanalytic. When analysts follow this formula—and only then—we might say the work of analysis bears some hope.